Medical Journals are Allergic to Data on Racism

July 13, 2021

Medicine’s Privileged Gatekeepers: Producing Harmful Ignorance About Racism And Health

Health Affairs Blog

April 20,2021

By Nancy Krieger, et al.

We conducted a literature search for … papers including the word “racism” that were published between January 1, 1990 and December 31, 2020 by four leading medical journals (all with impact factors for 2019 exceeding 30). These journals were: the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), The Lancet, JAMA, and the British Medical Journal (BMJ). We focused deliberately on the term “racism” because naming racism is a critical step in addressing its impacts. And given evidence of some journals censoring its use, this focus allowed us to assess the extent to which use of this term has been permitted.

For comparative purposes, we also searched publications in one of the longstanding and leading global public health journals, the American Journal of Public Health (AJPH), and we additionally examined the Annual Review series for four disciplines (medicine, public health, sociology, and psychology) as a gauge of the extant evidence base. . . .

The four medical journals published markedly lower numbers of papers including the word “racism” compared to AJPH, despite their publishing many more papers between 1990-2020 (14,192 for AJPH, vs. 40,411 for JAMA, 43,378 for NEJM, 63,971 for The Lancet, and 78,545 for BMJ). Although we did not include Health Affairs in this analysis, Rhea Boyd (one of the authors of this post) and colleagues noted in an earlier Health Affairs Blog post, “A quick search of the Health Affairs website reveals only 114 pieces include the word racism in the 39-year history of the journal.” . . .

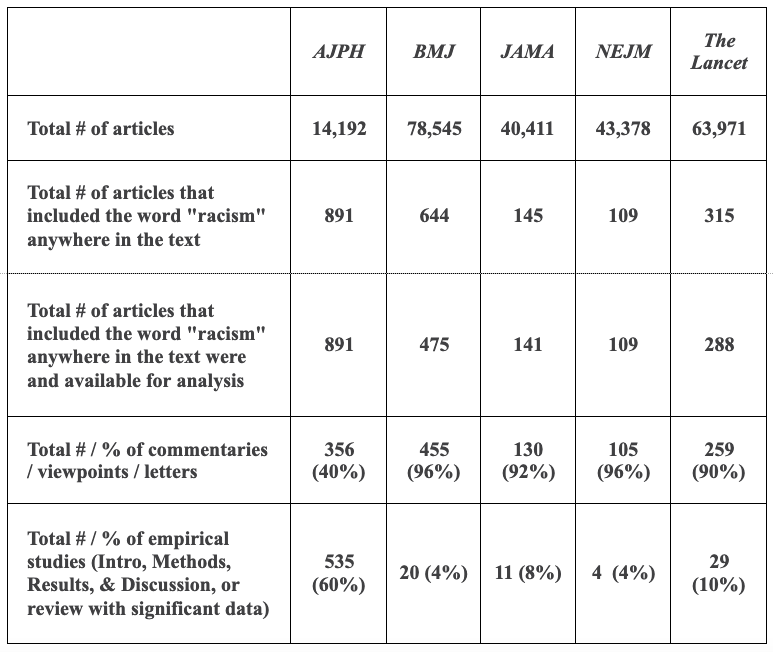

Exhibit 2: Analysis of article type for journal articles that included the word ‘racism.’

For the four leading medical journals, upwards of 90 percent of publications including the word “racism”… were commentaries, viewpoints, or letters. The percentage that were either original empirical investigations or review articles with a significant data component ranged from 4 percent (BMJ and NEJM) to at most 10 percent (The Lancet) (exhibit 2). By contrast, for AJPH, 60 percent of identified articles were empirical studies or review articles with significant data, and only 40 percent were commentaries, viewpoints, or letters. . . .

Non-publication of this research conveys the message that racism and its impact on people’s health are not important and not topics that warrant scientific study or publication, thereby minimizing concerns about these harms among scientists, funding agencies, and the broader public.

Second, non-publication of scientific research on racism and health by leading journals, especially in this era of evidence-based clinical medicine, fosters ignorance about these issues among health professionals, who as trusted sources of information then transmit this ignorance to their patients, clients, and the broader public.

Third, this non-publication of evidence undercuts and limits the important kinds of evidence needed by policy makers, health agencies, funders, lawyers, and advocates for their complementary work to prevent racism and rectify how it harms health.

Fourth, non-publication of this work effectively excludes scholars who study racism and health from high-impact journals, harming not only knowledge dissemination but also potentially the career pathways of these scholars.

Comment by David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler

In recent months younger colleagues and others we know have had several studies documenting stark racial inequities in health care rejected by major journals based on: (1) minor quibbles about methods that have not been raised about closely similar analyses of age-, insurance or income-based disparities; or (2) claims that race-based disparities may simply reflect overuse of care by White people, and hence are not indicative of racism.

Our experience is apparently not unique. This meticulous survey documents major medical journals’ refusal to publish data on racism. While the journals have accepted commentaries and letters on racism, they continue to boycott studies documenting the patterns of care and outcomes indicative of structural racism. So while we’re now allowed to say that racism in the health care system exists, we’re not allowed to provide the data that’s key to addressing it.

You might also be interested in...

Recent and Related Posts

Premier Medical Journal Scrutinizes Corporatization of US Health Care

Laying out the Ill-Effects of Medicaid Cuts in the Congressional Budget Bill